Ancient Chinese Year Calendars were introduced to Japan in the year 553, but it was not until the year 604 that the Japanese officially adopted them. This Calendar was based on the sexagesimal system (base 60) of the Buddhist 5(x2) Celestial Stems combined with the 12 Terrestrial Stems, giving 60-day cycles. There were 6 of these cycles in a year, thus totalling 360 days. Period adjustments had to be made to account for the difference to a true year of 365 ¼ days. The New Year started on the Japanese lunar new year day. This Calendar is still adopted today in some areas of interest, but now starts on 1 January.

During the Edo Period there were periodic attempts to reform the traditional calendar, partly under the influence of Western astronomy which had already been introduced to China by Jesuit missionaries. New Shogun observatories were built during the Edo Period and there was an ongoing political struggle for control of the calendar between the Shogunate and the Imperial court. After calendar reforms in 1685, the government controlled an effective monopoly on the production of printed calendars for the coming year, granting licences to a limited number of publishers under strict censorship.

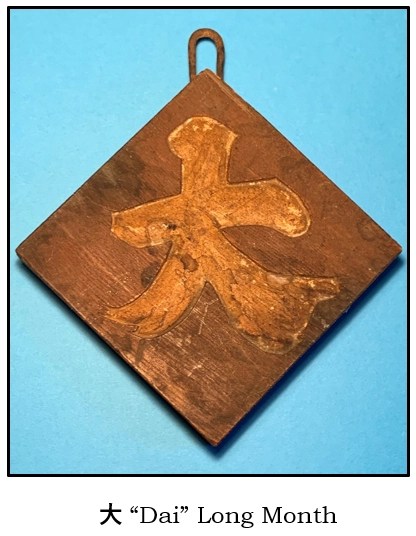

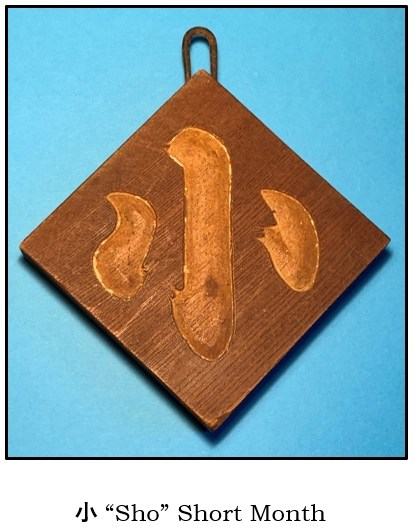

However, over the centuries and throughout the Edo Period, Japan generally adopted the system of 12 lunar months in a year. A lunar month corresponds to just over 29.5 days in the solar calendar. According to the official Japanese lunisolar calendar, each year had a different sequence of twelve either “long” (30 day) or “short” (29 day) lunar months. This had to be adapted about every three years or so with an extra, “intercalary month” (jun) added to synchronise with the seasons. Merchants, who made it a rule to effect payments or collections at the end of each month, would make plaques to show a long or short month and display them in their shops according to the month, to avoid mistakes. I was presented with a gift from Professor Kazuyoshi Suzuki, of the National Museum of Science and Nature, Tokyo, with one of these plaques at our meeting there in 2015 (below). It measures 12 cm x 12cm x 2 cm.

Wadokei Calendars

Wadokei with Calendars were first seen from around 1700. This date is only a few years after the government controlled reforms of 1685. Whilst the 12 lunar months of long and short months were used in daily life in Japan, Wadokei Calendars followed the Buddhist Stems convention. This was a continuation of using the 12 Terrestrial Stems adopted for Wadokei hours. In all probability, this would have been due to the fact that the time of day was rung-out by priests from Buddhist Temples to towns and villages. (This compares with the European Convention of using Roman Numerals for clocks).

In their simplest and earliest form Wadokei Calendars consisted of a single aperture in the front plate with a rear rotating engraved disc with the 12 Buddhist Terrestrial Stems. They later developed to having two windows with both the 12 Buddhist Terrestrial Stems combined with the 10 Buddhist Celestial Stems.

Double Aperture Calendars

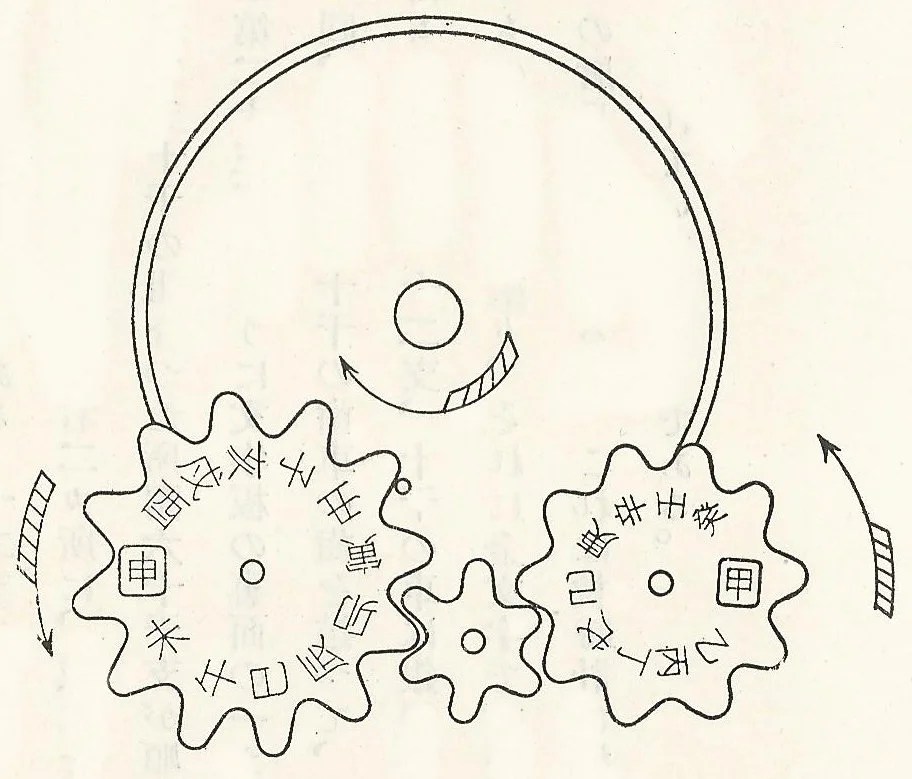

In the widely accepted 1960 book “Wadokei” by Taizuburo Tsukada, he states: that on the front of some Wadokei there are two small windows in which appear daily the combination of symbols for the Jukkan and Junishi the sexagesimal system of counting.

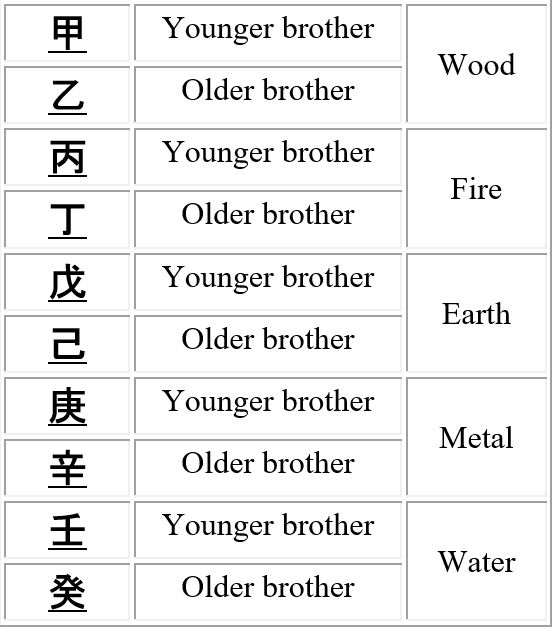

- The Jukkan uses the Buddhist 10 Celestial Stems of the five natural Branches of Wood (ki), Fire (hi), Earth (tsuchi), Metal (ka) and Water (mizu), each divided with the prefixes ‘Elder Brother’(Ki-no E) and ‘Younger Brother’ (Ki-no To). However, the words Ki-no-E and Ki-no-To are not commonly used; instead, the ten separate words Ko, Otsu, Hei, Tei, Bo, Ki, Ko, Shin, Jin and Ki are used.

- The x12 Junishi uses the Buddhist 12 Terrestrial Stems of Rat (ne), Ox (ushi), Tiger (tora), Hare (u), Dragon (tatsu), Serpent (mi), Horse (uma), Ram (hitsuji), Monkey (saru), Cock (tori), Dog (inu) and Boar (i).

Linking the Jukkan and Junishi engraved discs behind the front plate produces a full unique cycle of the 60-day month, with the 12 tooth Terrestrial Stem rotating 5 times, whilst the 10 tooth Celestial Stem rotates 6 times.

Single Aperture Calendars

Other Wadokei, particularly those of the Early Period, have a single aperture that shows the 12 Terrestrial Stems only and repeats 5 times in a 60-day month. This is the simplest form of naming the days. Some days were Lucky Days, and it was on these days that contracts would be signed and long-term purchases of equipment or works of art would be sold. Or, a day for buying a Wadokei!!

Tidal Time Windows

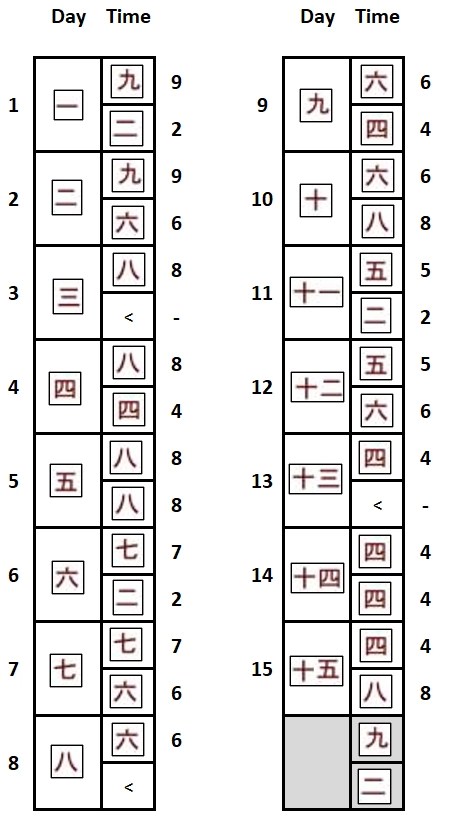

One of the Wadokei in my collection has double windows where one window shows a 15-day cycle with one or two kanji characters (1 to 10 in single characters, and 11 to 15 in two characters). The other window shows the time of day in a pair of kanji characters indicating the time of high-tide (michi) each day in hours and “bun” (1/10 of an hour in Edo Period).

With two high tides a day, and with a lunar month being 30 days (29.53 actual), the time of high-tides repeats every 15 days.

In some practices in Japan, of which some still survive today, there was a belief that certain ceremonies should be performed when the tide is coming in (flood tide sashi) a positive period of time, as opposed to when the tide is going out (ebb tide hiki) which was considered a negative period of time. Ceremonies in which the state of the tide is considered important, include: (i) naming a child on its birthdate, (ii) giving a child a symbolic gift on its first birthday, (iii) the marriage ceremony of san san-kudo, and (iv) the moving of a younger son, on his marriage, from the main house of his father to his own house. There were many other occasions when a flood tide was important, for example, the instance in which a boar is allowed with a sow in heat !!

Computation of the sequence of the time of high tide for each day in progression shows an increase in time each day of 4 bun.

However, for these time indications to make sense, it would rely on the user working to International Mean Time of equal hours where 4 bun would equate to high tide being 48 minutes later each subsequent day. The host Wadokei would not provide this as it is a Double Foliot Temporal time device. This probably indicates that the Wadokei is either a very late Edo Period example when Mean Time was available to many Japanese, but not Nationally adopted, or a post-Edo conversion to make use of a redundant Wadokei.