Number of Strikes

Candle clocks were one of the earliest methods for measuring time in Japan. These fuel clocks, which burned away would tell the priest when to ring the bell. Time was indicated by how much candle was left. This may have been the origin of why Early Japanese hours counted down and not up. No one knows exactly.

At first, six bells were used, one for each hour, but later in the 6th Century AD, complications arose since one, two and three bells were used to summon the faithful to prayer and other religious ceremonies. “9” was a lucky number originating in China, but also adopted by the Japanese. “9” was therefore chosen for mid-day and mid-night. This was followed by the six hours being followed by a count down to four bell strikes for each hour. Accordingly, the unusual assignment of the number of bell strikes for each hour was universally adopted across all Japanese striking clocks as 9-8-7-6-5-4 between midnight and noon, and noon to midnight.

However, the development and sophistication of Wadokei brought about the addition of half-hour striking. A unique feature of this Japanese form was the fact that half-hours were struck once after odd number hours and twice afler even number hours. Thus the full Wadokei striking sequence became 9-1-8-2-7-1-6-2-5-1-4-2.

Wadokei Strike Operational Features

As might be expected from the fact that Wadokei are based on early Dutch Clocks, there is no “warning” in the striking train, the old “flail” type of release being used in the early clocks and the “nag’s head” type in later clocks.

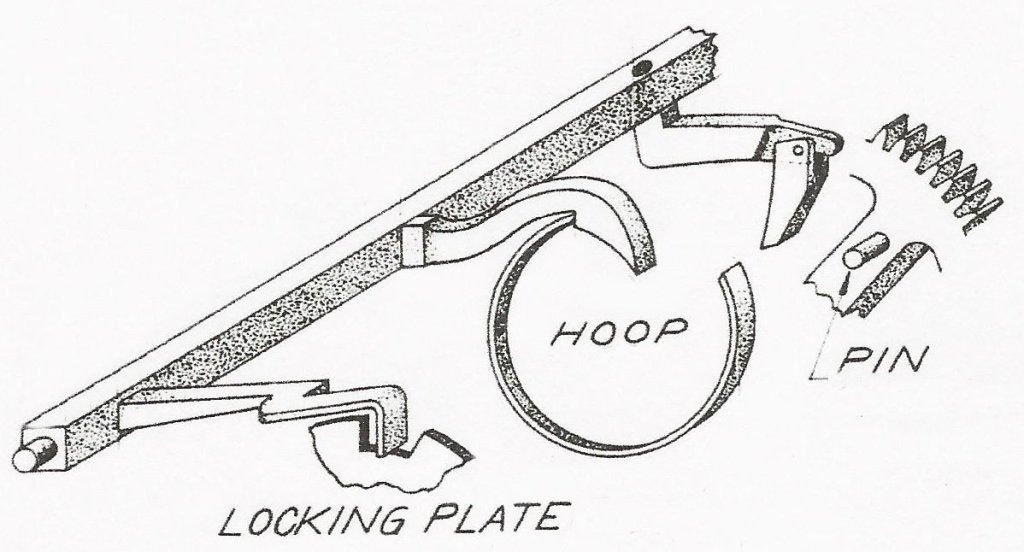

There are two other peculiarities; the fly, usually four bladed, has no slip but is pushed onto a squared arbor; and there is no heart-shaped cam for lifting the release out of engagement; instead there is a hoop wheel similar to those found in English lantern clocks and the inclined part of the locking arm is extended to give the required lift. The lifting pins for the hammer are on the great wheel whose arbor carries the pinion of report for driving the locking-plate. As in the European clocks of the period, the hammer is moved through an intermediate crank in the same plane as the bottom of the bell. About the only time the direct hammer action is found is in some but not all of the iron clocks.