Pillar Hanging Shaku-dokei Development

The method of measuring “hours” by the fall of the descending going weight from a Kake-dokei on the surface of the wall behind the Wadokei, led to the construction of small purpose made Wadokei with integral hour markers called Shaku-dokei. The name derives from the unit of linear measurement of the dial that was a “shaku” high (equating to approximately 300mm or 12ins.). Shaku-dokei were mainly made of Shitan (Cedar) wood.

The principle of Shaku-dokei was a unique Japanese invention. Many versions exist of this type of clock, that were made throughout the Edo-Period. Early examples first used the verge and foliot escapement, followed by the pendulum, and, in turn the balance wheel. The principle is the same in all the various types of shaku-dokei.

Shaku-dokei were simple and less expensive to produce than other types of Wadokei. Thus they became available to the more affluent public of the early 1800’s. They became relatively popular and certainly many have survived.

Early Basic Principle

Use of Falling Weight

Above is an early style of Shaku-dokei where the hour-markers are simply attached to a backboard and the falling going weight is a crude circular ring. The ability to provide any reasonable accuracy of time would have been impossible.

Late-1700’s Movable Hours

Adjustable Hour Markers

The first significant development of Shaku-dokei was to have vertically adjustable ‘temporal hour’ markers (plus half-hour markers on taller shaku-dokei) located in a groove running down a vertical dial plate. Each was held in place with spring plates to rear. A second vertical aperture enables a pointer (hand) fixed to the going weight to point to the appropriate hour. Thus as the weight descended the hours were indicated in succession. Temporal timekeeping was provided by appropriately adjusting the hour markers every thirteen days.

Late-1700’s Movable Hours

Single Dial with Stike

A similar example to that to the left but in this instance the dial is over two shaku (600 mm) tall. Further it has an additional slot to the left of the falling hand into which there is a rising carp. As the Going Weight and pointer hand descends the Carp rises. A rising carp is a an old Chinese / Japanese sign of success in life / business. Further, this Shaku-dokei is profusely lacquered with the Tokugawa nomon (crest) indicating that it was originally commissioned for a Tokugawa Shogonate’s residence.

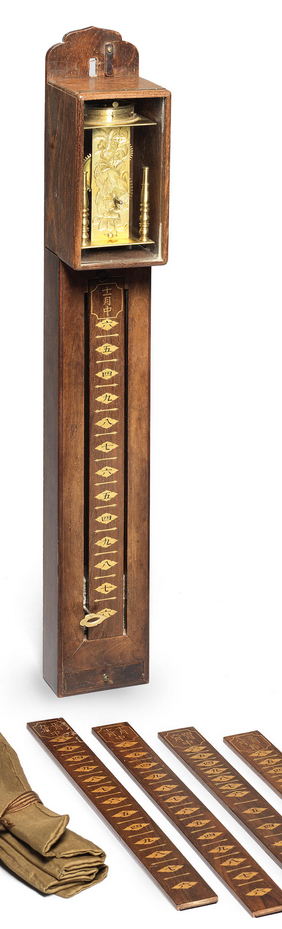

Late-1700’s Switchable Dials

Dial for each 14 days

A further more simple development was to have seven interchangeable dial plates, six of which had double-sided dials. Each of the 13 dials provided differing temporal hour scales. Typically a scale for mid-summer with long daylight hours could be used for mid-winter with long night hours. Changing the scales every 14 days covered two half years of 182 days i.e. 364 days of the year. Whilst not giving true astronomic year durations, it met the standards of the time and could be adjusted as required. This solution of temporal timing eliminated the need for the difficult task of adjusting vertical hour markers. Few complete sets of all seven plates exist, as usually a Shaku-dokei would find a new home with only the attached dial surviving.

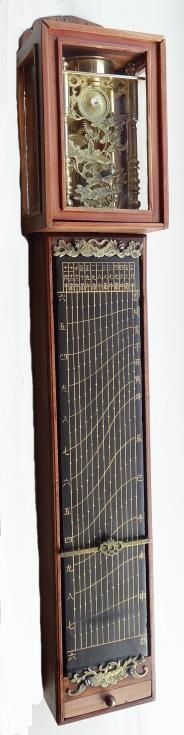

Post-1800 Graduated Dial

Graph for each 14 days

The next development was a single fixed dial plate with fourteen vertical divisions indicating temporal time for each of the 14 days of normal seasonal adjustments. These dials are called ‘Namagata’, as they resembled namagata, the Japanese for sea wave. Apertures on both sides of the dial plate enabled a cross bar to be fitted to either side of the Going Weight and to pass down the front of the dial plate. A sliding hand was fitted to this cross bar and could be positioned to indicate the hour for the appropriate 13 day divisions of the year. As with 7 dial plates (left), the scale for mid-summer with long daylight hours could equally be used for mid-winter with long night hours.

Post-Edo Dial

International Mean Time

At the end of the Edo Period and the introduction of Mean Time, it occurred to the Japanese Wadokei maker that these clocks might be adapted to the new system. Accordingly, instead of the Japanese set of Temporal Hour markers, a single scale was substituted that showed the time in equal hours commencing with twelve noon, and graduated through equal hours of twice-twelve hours. However, with the import of thousands of clocks particularly from the USA, plus the speedy capability of the Japanese to make clocks from tools purchased from the USA, these type of Shaku-dokei had no market.