Introduction

The Japanese adopted simple incense-burning methods for time measurement from China during the latter half of the 8th Century. Initially Japanese incense burners were crudely made in simplified versions of the more elaborate Chinese ones. Over the years the Japanese improved the incense clock into a more sophisticated device, formed upon a bed of finely sifted wood ash to provide greater consistency in the burning rate of the incense. It evolved into the ‘time measuring incense board’ or ‘time incense tray’ (jokoban).

The jokoban was originally devised as a means of continuing the burning of the sacred fire in Buddhist temples for limited time periods, such as through the night hours. It continued to be used for that purpose, but gradually it came into use also for the measurement of segments of time for prayer. By the Tokugawa period it served chiefly for timing the ringing of the temple bell.

In as much as the rate of burning of incense depends to some degree on the humidity and heat of the environment, the measurement of time by means of the jokoban was not entirely precise.

Koban-dokei Type A

One type of Koban-dokei is in box form. Made with two main parts; an upper section consisting of an incense tray in a square wooden box, and the lower section usually a cabinet having one or two drawers for the storage of utensils and an incense supply. A central wooden spacer allowed the top to rotate relative to the base and permitted re-orientation to assist in laying out the swastika design incense trail.

The lower cabinet had one or two drawers with brass pulls; the only metal used. Where there were two drawers, the upper was for the incense supply, and the lower for the utensils.

Several utensils were required for preparing the incense trail. All were made of wood.

- A template (variously known as kouke, kogata or koin) was used for forming the furrows of the incense trail through the template openings, consisting of five straight lines connected at one end by shorter straight lines at right angles.

- A wooden spatula (osae) was used to impress a groove in the ash bed through the opening in the template.

- A tamper (bainarashi) was used to flatten the bed of ashes.

Jokoban are often made of the wood of cryptomeria or of paulownia tomentosa steud, known to the Japanese as kiri, a tree introduced from China which is found throughout Japan. The light and soft wood is yellowish grey to light brown in colour, and does not warp or crack, and is incombustible. Another wood frequently used was keyaki (Zelkova serrata), a tree native to Japan, China, Korea and Manchuria.

The exterior of many jokoban was generally lacquered in black or red, or a combination of both. Occasionally, some were decorated also in gilt. The primary component of the Japanese incense seal is an incense tray in the form of a square box with a wooden latticework cover, which is fitted over the box framewith openings, for the emission of heat and smoke.

The ash was first flattened using the tamper. The incense trail was then formed a quarter segment at a time by locating the template on the edge of the upper section and using the spatula to create the groove. The template was firmly held in place while the powdered incense was added. The upper section was then swivelled on its central pivot to bring the next corner forward, and the above process was repeated until the swastica pattern was completed. It was said that neriko (paste incense) was used for ignition.

Small hour indicator plates, made of bamboo or metal, supported on wooden or metal rods, were inserted at regular intervals along the trail, each bearing the character for one of the twelve hour segments.

Koban-dokei Type B

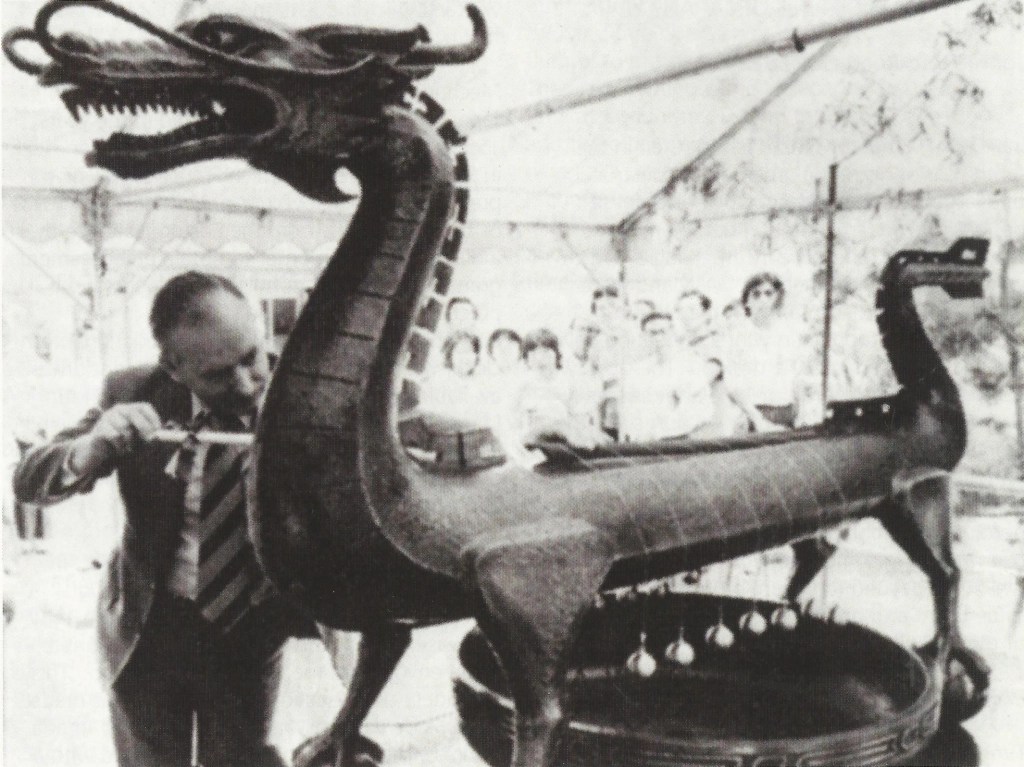

A second type of Koban-dokei popular in Japan was in the form of a dragon boat. The “boat” consisted of a carved wood body with figurehead and stern representing the head and tail of a fiery dragon. The central body was hollowed out to take a thin trail of incense. The device was supported on four carved dragon feet (note: Chinese dragons have five claws, whilst Japanese dragons have three claws). The interior was fitted with a pewter liner pierced at intervals with nine openings along its length into which are inserted V-shaped wires which serve as a rack for supporting an incense stick.

The dragon boat rested upon two pedestals. A metal pan or basin having a high resonance was placed between the pedestals on a flat surface. The “clock” consisted of a pair of small bronze bells tied to the terminals of 13 silk threads. The threads were draped over the incense stick at intervals corresponding to the rate of burning of the incense trail and the Temporal Hours of the Japanese day.

A good example of a large form of one of these clocks is well illustrated in a photograph of John Read (see ‘UK Past and Current Wadokei Collections’ page), then Managing Director of Rolex, South East Asia, at the Omi Jingu Shrine on Time Day 1979.

See also image on Home Page of Kazuo Murakami and myself next to this Dagon Clock in 2014.

Koban-dokei in my collection.

Left: c.1900 – Solid wood with bamboo nails. Smoke traces on underside of cover suggests extensive use. The polished finish and sheet metal handle suggests Meiji Period. Complete with two templates (koin) one apparently original and one later, spatula (osae) and tamper (bainarashi).

Right: c.1850 – Solid wood with bamboo nails. Smoke traces on underside of cover suggests extensive use. Traditional coloured lacquer central section. Forged iron handle style suggests manufacture 1850 – 1875. Complete with two template (koin) one apparently original and one later, spatula (osae) and tamper (bainarashi).

Below: Koin (original and replacement), plus osae and bainarashi.